“I watched over every note, paid attention to the right vowels on the high sounds, ensured a completely natural prosody, while allowing the voice to pour out to the fullest […] the recitative style is when you speak while singing; the lyrical style is when you sing while speaking!” said the prodigious and endearing Francis Poulenc about his Dialogues des Carmélites, regarding which he confessed to a friend: “I have never written a work with more enthusiasm. I live with all these Carmelites from morning to night in a state of fascination.”

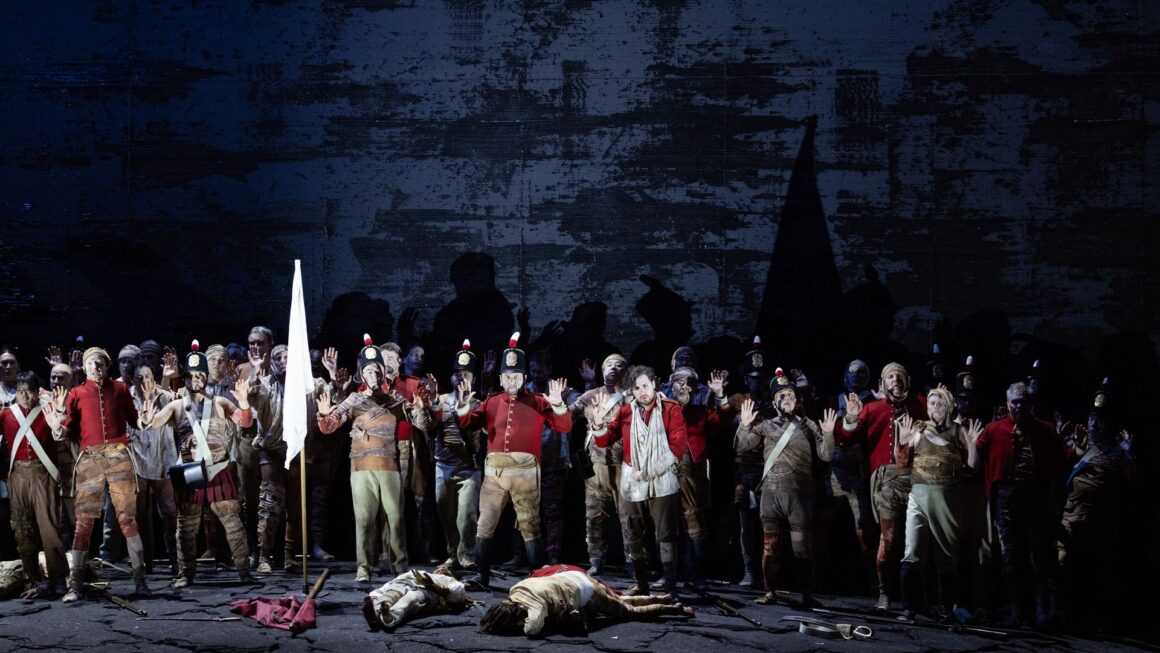

An immense challenge, then, to produce and perform this absolute and total masterpiece, a Gesamtkunstwerk par excellence, with a libretto as rich as it is profound—a synthesis of everything the operatic form has engendered that is beautiful and deep over the centuries. A challenge met at the Wiener Staatsoper, in the revival of Magdalena Fuchsberger’s production, by a cast that at first glance seemed not entirely obvious for the repertoire, yet ultimately proved more than satisfying. Let us take a closer look.

Bogdan Volkov’s Chevalier de la Force was the source of the evening’s first astonishment—right from the opening measures. And for good reason: his French is absolutely flawless, to the point that no native speaker could detect the slightest issue with diction. A crucial quality, particularly for this opera, a work of total theater where music is inseparable from speech. We already knew the Ukrainian tenor to be impeccable and exemplary in everything he undertakes; here we discover him profoundly respectful of a text that grips, shakes, and questions anyone willing to plunge into its countless angles. What an artist. May our beloved industry produce as many like him as possible, and as quickly as possible.

His Act II duet with Blanche is particularly poignant and provokes in the hall that kind of sacred silence only opera can generate—where every listener seems to walk a tightrope, like the two protagonists, like Poulenc’s music, where absolutely everything and everyone is at stake every second—the very concept of Gesamtkunstwerk, in short. Olga Kulchynska is just as responsible for this as he is, and more broadly, she carries the title role with dazzling solidity and aura. The text is fully integrated and internalized, and her theatricality allows her Blanche to be as touching as she is distant, as human as she is abstract, as coherent as she is paradoxical. Through superior intelligence and artistic instinct, her timbre and acting adapt without ever shifting too abruptly (her moving devotion in the initial duet with Madame de Croissy sounds nothing like her final existential hesitations), ensuring a coherence and diversity as rare as they are essential for a successful Dialogues.

As for the Carmelites, Sylvie Brunet-Grupposo’s Madame de Croissy is literally tragic and terrifying, both in what she radiates and in what she declaims. Drawing on her native French, the still-young singer seems crushed under the weight of a life of suffering and deprivation, paradoxically sealed by an infinitely painful death. The revelation of the evening is Maria Motolygina, portraying a Madame Lidoine both wise and resolute. The voice is already full and powerful, the timbre warm and brilliant, and every intervention captivates. Particularly her final aria in the prison cell—the penultimate step before the ultimate apotheosis—arguably among the most powerful, if not the most powerful, in the entire repertoire. Maria Nazarova makes Sister Constance as sparkling as she is endearing and touching; Julie Boulianne embodies a Mère Marie equally convincing—both authoritarian and passionate—just like Stephanie Maitland’s edifying Mother Jeanne and Teresa Sales Rebordão’s pragmatic Sister Mathilde. The cast is completed by Michael Kraus, a Marquis de la Force both noble and anxious; Jörg Schneider, a confessor as resolute as he is concerned; Andrea Giovannini and Simonas Strazdas as the commissioners; Alex Ilvakhin as the officer; and Andrei Maksimov as the jailer.

Robin Ticciati—decidedly as talented as he is promising—conducts a Wiener Philharmoniker at its finest, an orchestra that seems to have fully embraced this music and to defend it at all costs, asserting in the most convincing and concrete way its unofficial yet widely acknowledged status as the world’s most prestigious ensemble.

Nothing less is required to rise to the level of an absolute and total masterpiece—one that, according to a friend of Georges Bernanos (author of the original play), in addressing Poulenc: “You seem to me to have accomplished a tour de force in adapting the text to the demands of a musical work, while remaining absolutely faithful to its spirit and to the major lines of a very delicate architecture. It was no easy task to transpose into opera this plot nourished by profound themes and sustained by continuous meditation…” And evenings like this, served in such a way, connecting us intensely with the great existential questions—including death—paradoxically make us feel more alive than ever. Long live opera, long live Bernanos, long live Poulenc, and long live the artists worthy of such a summit.

*****

CAST

Blanche

Le Chevalier

Madame de Croissy

Madame Lidoine

Mère Marie

Le Marquis de la Force

Soeur Constance

Mutter Jeanne

Schwester Mathilde

Beichtvater des Karmel

Erster Kommissar

Zweiter Kommissar

Ein Offizier

Kerkermeister

Thierry

Michael Wilder

Javelinot

Panajotis Pratsos

Eine Frauenstimme aus der Kulisse

Irene Hofmann

Erste alte Frau

Amelle Parys

Zweite alte Frau

Sylvie Jubin

Ein alter Herr

Christian Lenoble

——-

Musikalische Leitung

Inszenierung

Magdalena Fuchsberger

Bühne

Monika Biegler

Kostüme

Video

Aron Kitzig

Licht

Rudolf Fischer