Wozzeck, Alban Berg’s masterpiece, turns 100. The first performance took place on December 14, 1925, at the Berlin Staatsoper, under the baton of the legendary Erich Kleiber. It was Kleiber’s determination, and his intense correspondence with Berg, that led to the opera’s success, requiring more than 150 rehearsals amid protests from the singers and the Orchestra, who deemed the score unperformable, and a press campaign unleashed by the reactionary press. Between 1925 and 1932, the opera was performed 21 times at the Staatsoper and premiered in major European and North American cities.

During the Nazi period, the opera was banned in Germany because Berg’s compositions were considered “ertartene Kunst” namely degenerate art. Wozzeck is definitely one of the most emblematic opera of the period between the two world wars; Wozzeck exemplifies the themes of social criticism, existential alienation, and the most radical aspirations of new music, specifically those of the Viennese School. The opera was a long process of composition, beginning on May 5, 1914, when Berg attended a performance of Georg Büchner’s play Wozzeck and was struck by it. The libretto divided the drama into three acts of five scenes each.

To intensify the stage action, Berg conceived the opera as a system of closed forms, in which each of the 16 scenes constitutes an independent structural unit and uses a baroque or classical musical form (rhapsody, march, passacaglia, fugue, etc.). The unifying element is provided by the network of Leimotives associated with the individual characters and dramatic situations, and by the use of highly dramatic vocal forms, particularly the “Sprachgesang,” a technique of producing notes halfway between singing and acting. “Das ist eine Oper! Eine echte Theatermusik!” “This is an opera! A true theater music!” exclaimed Arnold Schönberg, Berg’s teacher and mentor.

The theatricality of this atonal opera is precisely what accounts for the success and the presence in the repertoire of the tragic story of the poor soldier Wozzeck. To support his companion Marie and their son, he submits to the humiliations of the Captain and the cruel experiments of a Doctor, developing hallucinations and paranoia, ultimately leading to his jealous murder of Marie, seduced by a presumptuous Drum Major, and his suicide in a frozen lake.

The Staatsoper unter den Linden celebrates its centenary with a luxurious performance, rewarded by a sold-out audience. Under the baton of Generalmusikdirektor Christian Thielemann at the head of the Staatskapelle Berlin and a stellar, near-perfect cast, this performance was one of the unmissable events of the current season. Wozzeck is an opera for superstar conductors, among which we remember Karl Böhm, Pierre Boulez, Claudio Abbado, and Daniel Barenboim. Thielemann, who just two days earlier had conducted a sparkling New Year’s Concert with music by Franz Lehàr, delivers an impressive performance from every perspective. The score reading is pure glass, and the Orchestra produces a crystal-clear soundscape in which every instrument and timbre is recognizable, from the violins to the brass, from the harps to the celesta, and even the accordion on stage in the ballroom scene. Thielemann masters perfectly the six-seven- part polyphony, the different rhythmic structures of the scenes, and the sound dynamics, pushing the orchestra to a fortissimo that shakes the theater.

The orchestral interludes become part of the narrative, giving dramatic structure to the action, further enhanced by the choice to perform the opera in continuity, without pauses between the three acts. In the title role, we find English baritone Simon Keenlyside, who portrays a neurotic and delusional Wozzeck, moving on stage like a wounded animal, humiliated by the harassment of his tormentors and Marie’s betrayal. Vocally, Keenlyside masters the challenging vocal writing, with a consistently clear and crisp delivery that reflects his great Mozartian background while simultaneously embracing all the nuances of expressive singing of Sprachgesang.

Anja Kampe is a phenomenal, anthology-worthy Marie; her dramatic soprano voice soars in the high notes and descends into the low notes with dark, expressive tones, portraying a controversial character poised between maternal instinct and the desire to enjoy life to the full, alternating between desperation and erotic and sexual energy. Andreas Schager is a Tambourmajor of great vocal power, a Heldentenor portraying this arrogant and overbearing character, who voluptuously dances with Marie and possesses her before his son’s eyes.

Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke‘s Captain is extraordinary; his use of Sprachgesang and high falsetto notes exceptionally delineate the character’s hysterical insecurity and comic caricature.

Stephen Milling‘s Doctor is also excellent, a character portrayed in a radically negative light both by Büchner—who had a background in medicine—and by Berg; these “immortal experiments” foreshadow the horror of those of the Nazis in the extermination camps. Florian Hoffmann, as Andres, Wozzeck’s comrade-in-arms, and Anna Kissijudit, portraying Margret, with a temperamental mezzo-soprano voice, are also perfect in their roles.

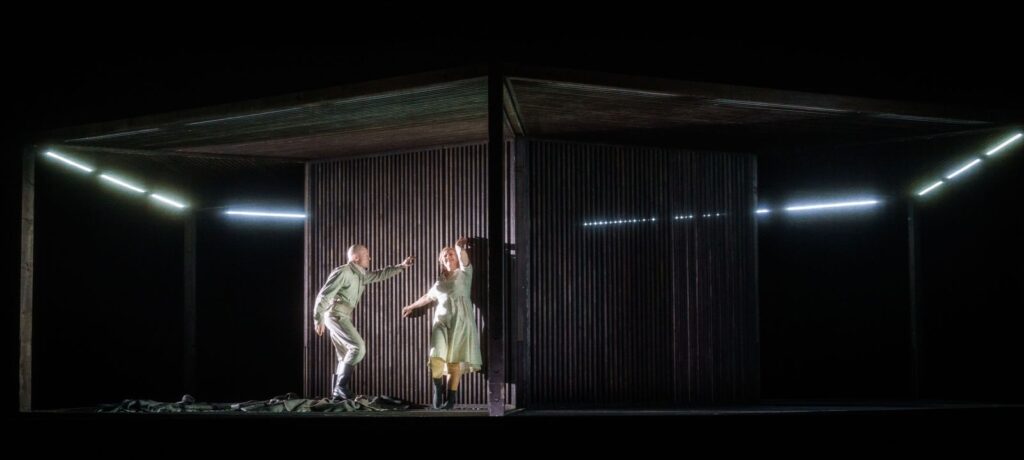

The staging doesn’t quite reach the exceptional levels of the musical performance; for the occasion, a 2011 production directed by Andrea Breth is being revived. The minimalist production accentuates the claustrophobic and anguished quality, conveying the suffocating and oppressive atmosphere of the drama. For a good half of the opera, the stage is occupied by small pentagonal cells, with barred windows that amplify the dramatic confrontations between the characters. Halfway through, a hexagonal structure is revealed, which in the ballroom scene houses the small orchestra in the upper section, perhaps the show’s most successful aspect. During the interludes, the scenes disappear beneath a black curtain, like the darkness that engulfs the characters, revealing a vast, bare stage in the scene where Wozzeck slits Marie’s throat with his knife. The hexagonal structure becomes the carousel in the last scene, around which Marie’s son innocently plays with the rocking horse, next to his mother’s corpse.

A memorable evening, a huge success with the public, and a musical outcome that can be considered unforgettable in the history of the interpretation of this twentieth-century masterpiece.

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

CAST

Wozzeck: Simon Keenlyside

Marie: Anja Kampe

Drum major: Andreas Schager

Andres: Florian Hoffmann

Captain: Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke

Doctor: Stephen Milling

Margret: Anna Kissjudit

First apprentice: Friedrich Hamel

Second apprentice: Dionysios Avgerinos

Madman: Stephan Rügamer

Solist des Kinderchors der Staatsoper

Musical Director: Christian Thielemann

Director: Andrea Breth

Revival director, assistant director: Caroline Staunton

Set Design: Martin Zehetgruber

Costumes: Silke Willrett, Marc Weeger

Light: Olaf Freese

Chorus Master: Dani Juris