First and foremost, you have to disobey: that’s the first duty when the order is threatening and cannot be explained. (Ariane et Barbe Bleue or La Délivrance inutile, act 1.) This citation is enough to quickly and aptly describe the thread that runs through the triptych that opens the new opera season at the Opéra National de Lorraine, in Nancy. The project combines three pieces that are , if not completely unknown, at least unfamiliar to the general public: Paul Hindemith’s Sancta Susanna, Béla Bartók’s Bluebeard’s Castle and Arthur Honegger’s La Danse des Morts.

© Jean-Louis Fernandez

What do they have in common? Their structure around the woman (l’Héroïne, in the singular, from her baptism, through her marriage and on to her death) who has the courage to infringe the dictates to which she is subject, “at the three ages of [her] existence”, as the program underlines. This resolutely daring production is the fruit of a collaboration between Korean conductor Sora Elisabeth Lee (nominated in the “Révélation, chef d’orchestre” category at the 2023 Victoires de la musique classique awards) and director Anthony Almeida (winner of the European Opera Director Prize).

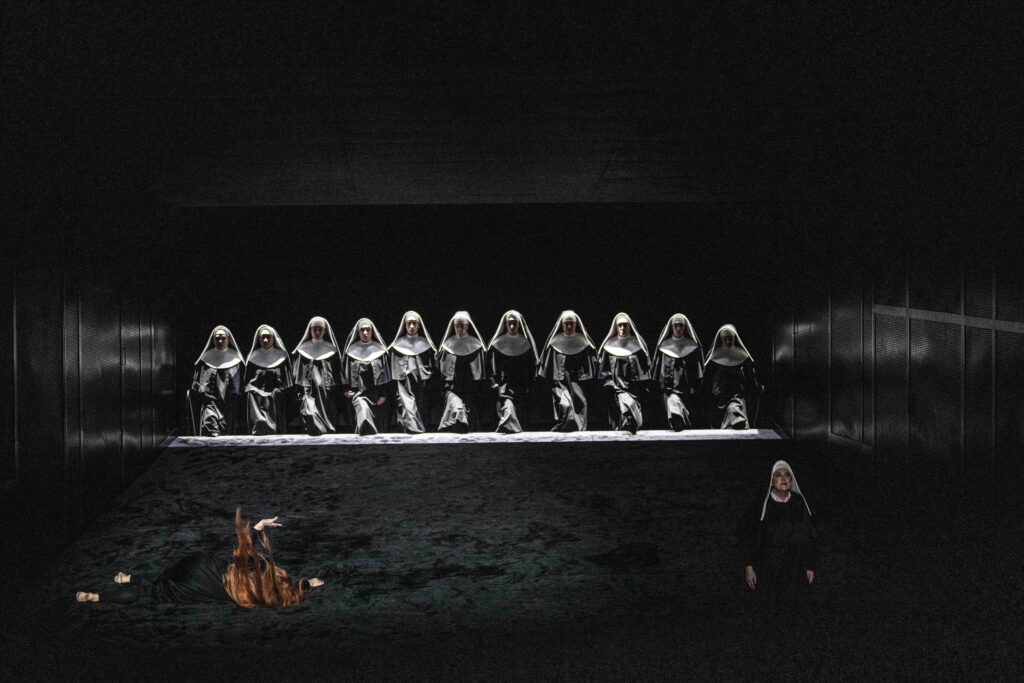

Sancta Susanna is the 3rd opus in one act of a triptych (the other two pieces are Mörder, Hoffnung der Frauen and Das Nusch-Nuschi) composed by Paul Hindemith, then aged 26. Of these three, Sancta Susanna, composed in only 15 days in 1921, is the most sulphurous. The story recounts the unspeakable sexual fantasies of Susanna, a young nun who, after having surprised a couple in the convent gardens, is seized by an irrepressible desire for the crucified Christ in the chapel. Cursed by her companions with the cry of “Satan”, victim of the damnation she had uttered against the valet and the maid and of that which had led to the imprisonment of another nun 40 years earlier, Susanna also gives herself over to her sexual madness, stripping naked to embrace Christ at the end of the opera.

© Jean-Louis Fernandez

In Anthony Almeida’s (highly chaste) version, the conflict goes beyond whether or not to give in to concupiscence: Susanna (Anaïk Morel, a mezzo of real power and capable of vocal acrobatics executed to perfection) claims, with an increasingly violent frenzy, an absolute freedom whose incompatibility with the asceticism of her environment, crystallised in the attitude of Schwester Klementia (Rosie Aldridge who, despite the indisposition she suffered during the performance, displayed a vigorous timbre capable of both a marmoreal coldness and a passionate voluptuousness, appropriate to the character’s poorly repressed bestiality). We particularly salute Rosie Aldridge’s somewhat Straussian madness (particularly towards the end of the opera, during the monologue Beata, beata, beata) and Anaïk Morel (with demented joy as she launches her So helfe mir mein Heiland gegen den euren! over the raging orchestra). The growing shudders that Susanna provokes in Klementia throughout the work are not synonymous with fear or abhorrence, but the beginnings of a lasciviousness that Klementia had denied all her life.

© Jean-Louis Fernandez

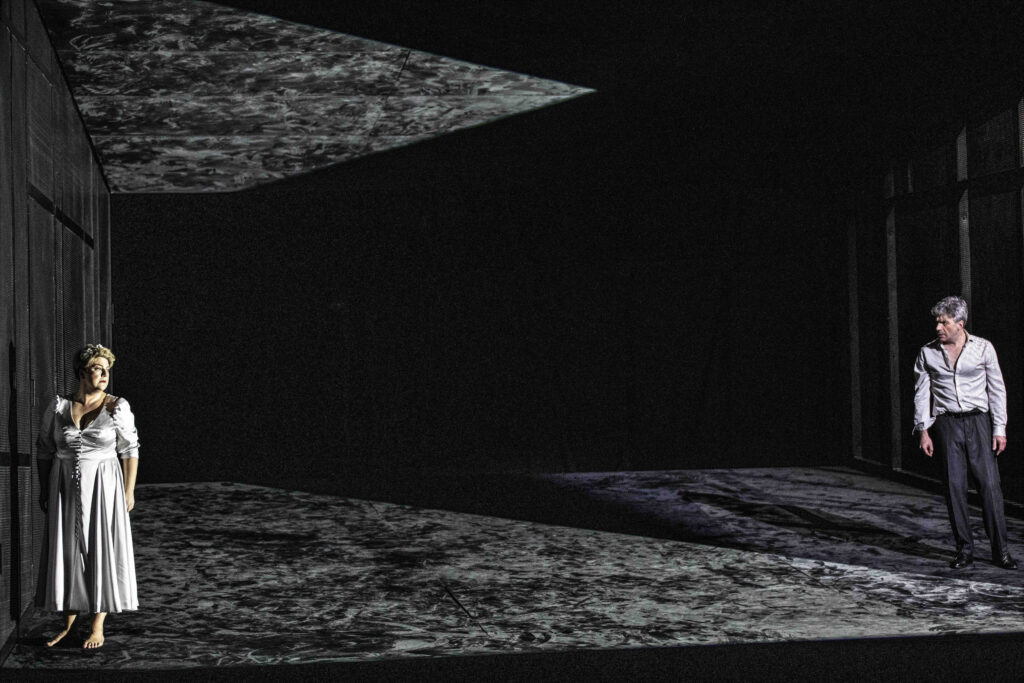

Bluebeard’s Castle (A kékszakállú herceg vára, literally The Blue-Bearded Duke’s Castle) is the only opera composed by Béla Bartók. This old Breton legend crossed with the life of Gilles de Rais had, since Perrault, been set to music by Grétry, Offenbach and above all Paul Dukas (to a text by Maeterlinck). Bartók sought to reduce operatic conventions to a minimum. No interval, with the action condensed into 1 hour, led by a bass (Joshua Bloom, a performer of great finesse who imbues his interpretation with a tenderness of wonder as well as a vampiric, sometimes libidinous darkness, as in his Gyere, gyere, csókra várlak!) and a mezzo-soprano (Rosie Aldridge, indefatigable, despite the segue into Sancta Susanna; such a linguistic and (above all) technical feat – crowned by a fiery high C to the violent orchestral tutti when the fifth door opens – could only be achieved by such a complete and versatile artist). The “hero’s” other wives are secondary, mute figures (they make only a very brief appearance at the end of the performance). There is no action (except psychological), reinforced by the metal bars of the cage where the two characters are locked up and the play of chiaroscuro created by the movement of the stage set. A static opera if ever there was one, but one that is fraught with meaning, structured around constant changes in the relationship between the two characters, at once predator and prey. The work is nothing more than a continuous recitative, a mixture of unspoken words and stolen revelations: the music progresses like a sometimes untameable river (often both singers must find the resources to overcome the devastating power emanating from the pit), constantly renewing itself. Sora Elisabeth Lee’s chiselled musical direction, thought out down to the last note, reveals the content of each open piece with a lucidity that is both poetic and harsh, despite the austerity of the staging.

© Jean-Louis Fernandez

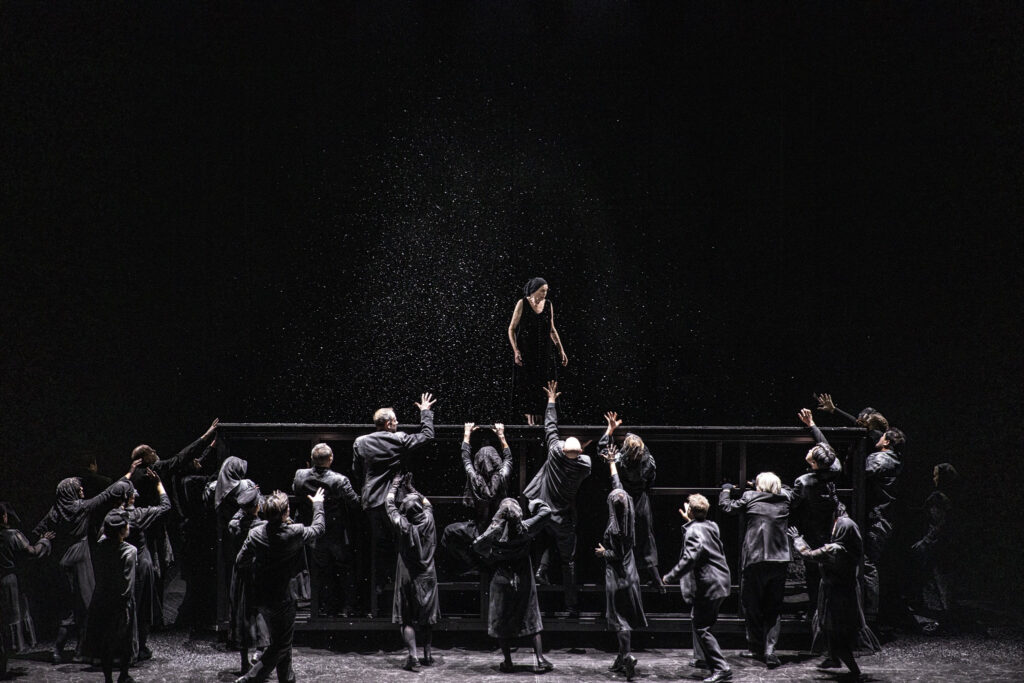

La Danse des Morts, an oratorio by Arthur Honegger – first performed in 1940 to a libretto by Paul Claudel -, is a sacred cantata for narrator, soloists, organ, choir and orchestra. Claudel was inspired by the engravings of Hans Holbein (a German Renaissance painter and engraver), in which the “dance of the dead” alludes to the macabre dances frequently performed in the Middle Ages, the purpose of which was to remind Christian believers that they are nothing but dust, whatever their social position. In the specific case of Honegger’s work, the Dance’ frees itself from any demonic presence to return to biblical reality (a prophet has a vision of the resurrection of the bodies), emphasising the fragility of human destiny in the face of divine greatness. The driving force and power of this oratorio are provided by the members of the Conservatoire Régional du Grand Nancy, whose breathless performance is supported by a majestic orchestral accompaniment. It is in this third part of the triptych that the theatrical resources are the most accomplished : thanks to the mass effect that the choir, the (luminous) intervention of Claire Wauthion in the role of the woman and the other singers embodying the Heroïne offer to the representation, we witness a beautiful parlée-chantée performance.

This astonishing, surprising, ambitious and exciting production not only inspires the best comments (from audiences and critics alike) but also the hope that other opera houses, in France and elsewhere, will come up with similarly well-produced and intelligent productions that will enjoy the same success.

Casting :

Sancta Susanna: Susanna (Anaïk Morel), Klementia (Rosie Aldridge), a maid (Apolline Raï-Westphal), an valet (Yannis François), an old nun (Séverine Maquaire).

Bluebeard’s Castle: Kékszakállú (Joshua Bloom), Judit (Rosie Aldridge).

La Danse des Morts: Alto (Anaïk Morel), Soprano (Apolline Raï-Westphal), Baryton (Yannis François), a woman (Claire Wauthion), a little girl (Salma-Faïhrouz Jacquot Anseur), Conservatoire Régional du Grand Nancy.