Moussorgsky’s Chowanschtschina stands as a singular achievement: a human comedy transposed into music, a vast operatic river whose currents are as intricate as Balzac’s narrative designs. Rarely performed, its very appearance on stage constitutes an event of stature. As Alain Duault observed in his introduction to L’Avant-Scène Opéra (issues 57/58), everything here is driven to its highest pitch: vehement monologues, prophecies and mystical visions, impassioned duets, and choruses of striking power, steeped in the sonorities of Orthodox liturgy. For three hours the listener is borne along in a torrent of intensity, wandering across the steppes in contemplation of the peoples evoked. Though Moussorgsky gives voice above all to the dispossessed, it is the full spectrum of a society rich in diversity that emerges in this immense fresco: an opera that overwhelms by its scale and sears by its truth.

As we learn from L’Avant‑Scène and André Lischké’s authoritative Guide de l’opéra russe, it was the critic Stassov (Moussorgsky’s long‑standing friend) who first provided the composer with the idea and the framework for what would become Chowanschtschina. In Stassov’s conception, the work was essentially historical. Yet an overly scrupulous fidelity to dates and facts would have prevented Moussorgsky from defining his subject with clarity, while rendering dramatic development and completion almost impossible. Hence, although the opera rests upon a historical backdrop, its adherence to events is far from exemplary in the staging we witness in Berlin. What remains, however, is the founding principle: the story of a Russia torn between ancient powers and reform, culminating in the tragedy of the vanquished.

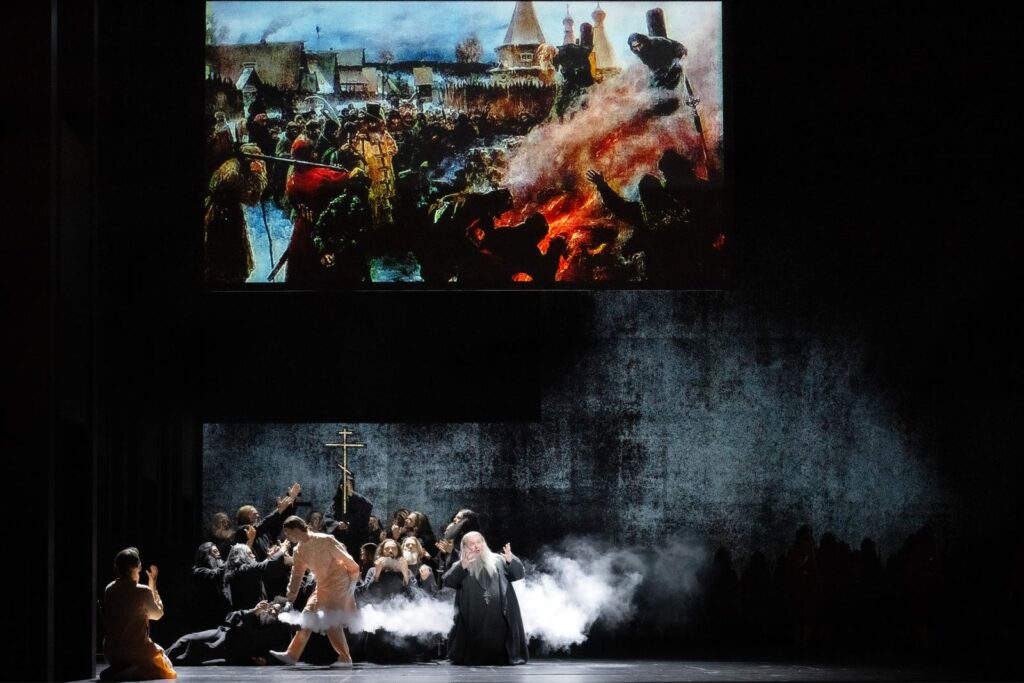

Thanks to Claus Guth’s pared‑back staging, we witness both the Russia of deep tradition, with its harsh customs, ecstatic religiosity, tyranny and monolithic figures, and the Russia increasingly shaped by European influence, each unfolding seamlessly upon the stage. In parallel, those who contribute to the recreation of the five acts are themselves visible, their presence evolving as the opera progresses until they become part of the drama and suffer its consequences. The superb live video work of Jan Speckenbach and Marlene Blumert allows us to scrutinise the faces of the characters at close quarters: their anguish, their madness, their joy, all perfectly attuned to the musical transformations rising from the incandescent pit.

Timur Zangiev’s conducting is nothing short of sumptuous, from the very opening prelude, sumptuous in its gentleness and tenderness, a true sunrise over the Moskva as inscribed in the score. Every sonic landscape is present in this subtle, delicate reading, with tempi so finely balanced that contrasts gleam in all their brilliance, yet imbued with the requisite power whenever the music demands it. On equal footing with the orchestra and soloists, the extraordinary Staatsopernchor, under the direction of Dani Juris, assumes the mantle of the drama’s true protagonist: a people bowed down by suffering, yet a people whose presence carries equal weight in the unfolding of events that herald the (both political and spiritual) twilight of old Russia.

Mika Kares works wonders in the role of Iwan Chowanski. He commands the stage while retaining the humility to listen to those around him. His voice radiates, one of those miracles capable of carrying across the Russian steppes and embodying the very call of destiny. Noble at first, he gradually transforms into the darkest of figures, a metamorphosis rendered with credibility and shading that restores to Iwan the full measure of his inner darkness. Thomas Atkins brings Andrei Chowanski to life with a blend of delirium and cynicism disguised as gallantry, yet never at the expense of vocal authority, particularly in his confrontation with Iwan. His obsession with Emma is finely counterbalanced by Evelin Novak’s lyrical and refined portrayal, her ease in the extreme upper register perfectly capturing the anguish of her character.

Evgeny Akimov’s Golizyn inhabits a realm of ambiguity, his commanding vocal modulations and theatrical flair faithfully conveying the character’s inner dualities. George Gagnidze proves as exasperating as Schaklowity demands, yet he refuses to settle for a mere embodiment of villainy: beneath the darkness lie suspicion of all and a capacity to reposition himself as circumstances shift. Such complexity can only be achieved by an interpreter able to assume the role with true authority. Authority, indeed, is the defining quality of Taras Shtonda’s Dossifei. More political than apostolic at the opera’s outset, he leads the people towards one of the most searing auto‑da‑fé in the repertoire, his burnished, otherworldly bass and incantatory ecclesiastical language delivering the full measure of power expected from a figure of such stature.

It is through Marina Prudenskaya’s Marfa that the work’s vein of lyricism and tenderness is truly quickened, without relinquishing the aura of enigma demanded by the character’s mysticism. Her divinatory aria in the second act with Golitsyn chills the listener with dread, heightened by the orchestra’s masterful rendering of sinister chromatic figures. Andrei Popov, inhabiting the role of Schreiber, emerges as the opportunist who manoeuvres through circumstances to preserve himself, even at the expense of others. For this, he wields a steely timbre, a voice that cuts with uncompromising force, eschewing any softness or lyrical indulgence, and underpinned by a resolute dramatic presence. A similar impression is left by Anna Samuil, though in her case it is Susanna’s fanaticism that lends her imprecations a harrowing violence, while still enveloping them in a sonorous, almost seductive vocal line.

With a succession of lyrical tableaux in which politics and both individual and collective emotions are summoned and embodied upon the stage, this work, alas still too little known, finds in the Staatsoper Berlin’s production the occasion, once and for all and with unanimous conviction, to be elevated to the summit. It is carried there by the exquisite and perfectly balanced quality of its cast, orchestra, and staging. A truly great moment for a truly great work.

******************************

Chowanschtschina

Volksdrama in fünf Akten (1886)

Musik und Text von Modest Mussorgsky

Fassung von Dmitri Schostakowitsch mit dem Finale von Igor Strawinsky

Musikalische Leitung | Timur Zangiev · Inszenierung | Claus Guth · Szenische Einstudierung/Spielleitung| Caroline Staunton · Bühne | Christian Schmidt · Kostüme | Ursula Kudrna · Licht | Olaf Freese · Choreographie | Sommer Ulrickson · Video | Roland Horvath · Live-Kamera | Jan Speckenbach und Marlene Blumert · Einstudierung Chor | Dani Juris

Fürst Iwan Chowanski | Mika Kares · Fürst Andrei Chowanski | Thomas Atkins · Fürst Wassili Golizyn | Evgeny Akimov · Bojar Schaklowity | George Gagnidze · Dossifei | Taras Shtonda · Marfa | Marina Prudenskaya · Emma | Evelin Novak · Schreiber | Andrei Popov · Susanna | Anna Samuil · Warsonofjew | Roman Trekel · Kuska | Junho Hwang · Streschnew | Johan Krogius · Zwei Strelitzen | Hanseong Yun und Friedrich Hamel · Staatsopernchor · Kinderchor der Staatsoper · Staatskapelle Berlin

(For further informations) Link to the Staatsoper Berlin website: Chowanschtschina

Thank you for sharing this wonderful review of the Staatsoper Berlin’s production of Chowanschtschina. It was a pleasure to read such a detailed and insightful critique, capturing both the epic scale of Mussorgsky’s work and the specific brilliance of this performance.

My question is about the production’s unique staging. The review mentions that the contributors recreating the five acts are visible on stage and eventually become part of the drama. Could you elaborate on how this directorial choice by Claus Guth affected your experience of the opera’s central theme—the tragedy of a people caught between old and new Russias? Did this modern, self-referential layer deepen the historical narrative or create a compelling tension with it?