It was not the rising of the curtains but their sudden fall, like the proclamation of an Old Testament prophecy, that summoned tragedy onto the stage. Centred upon Agamemnon’s tomb and framed by a metallic, near‑industrial set, the staging strives to embody a vision of morbid decline, driven by an unrelenting surge from the pit. It leaves no lingering sense of loss for the alternative productions rooted in Harry Kupfer’s celebrated mise en scène — one thinks in particular of Claudio Abbado’s famed 1989 account, with Brigitte Fassbaender as Klytämnestra, Eva Marton in the title role, and Cheryl Studer as Chrysothemis.

Dominating the stage stands a towering, anthracite‑grey statue, decapitated and monumental, eclipsing any evocation of the palace where Castor’s sister holds court. Not far from it lies the severed head of the condemned man: Agamemnon. As an allegory of the tomb invoked in the libretto, it is around the statue’s feet that the drama unfolds: the altar of Klytämnestra’s sacrifices, the site of Elektra and Orest’s reunion… Ropes are drawn into play, on which the characters haul themselves and one another, binding them together in a web whose dark epicentre is the king murdered in his bed, until Agamemnon’s daughter is finally strangled in the throes of her cathartic dance.

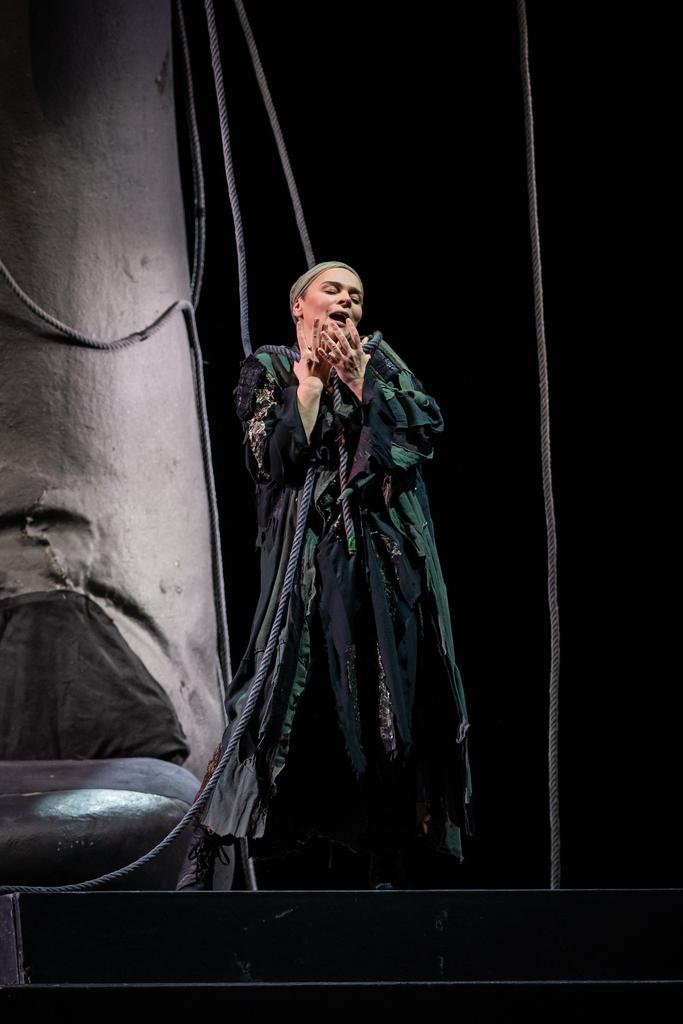

Aušrinė Stundytė inhabits a character of shifting hues, and within any single shade she can unfurl an entire spectrum of nuance. It is precisely in this refusal of binaries that her artistry blazes most brilliantly. Savagery? Certainly, but far, far removed from the vaguely barbaric strain that Götz Friedrich’s 1981 film taught us to associate with the role. What she offers instead is a violence of intention, a fissuring resentment, the very trait that will lead her to her own collapse. Her savagery takes shape in the gradual crumbling of the inner self, in its calcination under the weight of past and present traumas. To escape the stereotype of a feral, noxious creature, she draws on the resources of pure expressionism, moving with ease from contorted grimace to touches of the burlesque. A firm believer in “less is more”, she asserts her supremacy through the minutiae of her craft: a glance, a tilt of the head, a chosen inflection delivered with immaculate control, and thus establishes herself as the most fully realised Elektra of our time. When, in her opening monologue, her hands rise as she utters Agamemnon, followed by an ethereal wo bist du, Vater?, she reveals the almost spiritual dimension that the fulfilment of vengeance holds for her: a sensation confirmed later in the evening during her encounter with Orest. The Traumbild evoked here becomes the idealised, almost Wagnerian projection of her destiny finally within reach. In the vocal combat that pits her against more than a hundred musicians in the pit, there can be only one victor — and from first note to last, it is she. Her tone is razor‑edged, impetuous, yet capable of clothing itself in tenderness and softness in the monologue. Genius, virtuoso, phenomenon? A measure of each, and something more: the ability to shape the vessel to the force of its dramatic and musical content, and to raise upon the stage the Palast von Mykene we longed to behold.

Camilla Nylund gives life to an oppressed Chrysothemis, searching – and failing to find – a path that might offer her a glimmer of hope between the two titans who hem her in. We are left spellbound by the candour of her emotion and the freshness of her innocence, a perfect counterpoint to the stain of darkness, the scent of doom that Aušrinė Stundytė trails in her wake. Only the voice of a fully fledged Kaiserin could so powerfully and so clearly project this yearning – vital yet scarcely audible amid the moral and emotional wreckage that surrounds her. Like her colleague, she proves entirely capable of confronting the orchestra and even outpacing it, erecting in the process a wall set against the damnations and anathemas hurled by her elder sister, without ever sacrificing the complementarity essential to their relationship.

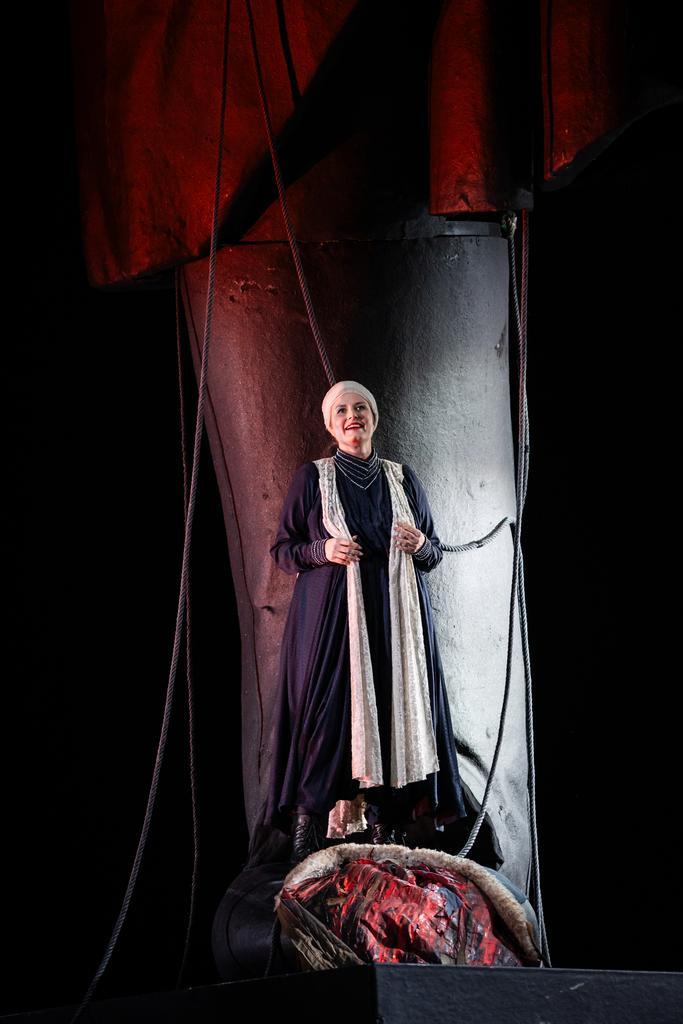

It is with a very particular pleasure that we hear and behold the great Nina Stemme assume the role of this fallen, festering goddess. The chest‑laden depths are delivered with the weight the character demands, yet it is above all in the upper register — recalling the Isoldes, Brünnhildes and Elektren who have traversed this unique dramatic and vocal terrain — that our delight is greatest. In this portrayal, rich in colouristic shadings from terror to vengeful derision, what emerges is not mere wickedness: it is malice, sarcasm, an oppressive intransigence laced with a strain of imperial cruelty, qualities that could scarcely fall more fittingly to one of the foremost artists of her generation.

Derek Welton upholds his Orest with admirable vigour, the voice richly grained yet elegantly projected, its timbre in perfect accord with the character’s temperament, despite a certain immobility. Yet this very immobility confirms, at least in his sister’s eyes, the sole reason for his return to the palace of Mycenae: he is the one who performs the fatal — perhaps redemptive — act, driven solely by the destructive energy radiating from Elektra. Jörg Schneider unfurls his silvery timbre in an Aegisth rendered more laughable than ever, as is so fitting in the Straussian repertoire. Foolish, pedantic, he gathers together all the traits that befit the most abject of cowards.

Under Alexander Soddy’s more inspired‑than‑ever baton, the Orchester der Wiener Staatsoper becomes a sonic mass capable of all but engulfing the stage, only to contract moments later into the most caressing and delicate of utterances. Such musical plasticity is possible only under a direction intelligent enough to instil in the players this endlessly renewed capacity for compression and release, for rebound and plunge, while maintaining an unshakeable through‑line. The reading that emerges from this profoundly analytical approach brings the score unabashedly close to Gurrelieder, even to Die Seejungfrau: post‑Wagnerian luxuriance at full stretch and oceanic surges yielding passages of incandescent lyricism.

With the revival of this legendary production, and a cast every bit as resplendent as that of earlier days, the Wiener Staatsoper is not attempting to make something new out of something old, but rather to show that with the new, it remains entirely possible to equal – indeed to surpass – what its stage has witnessed at so many moments of its history.

******************************

ELEKTRA

Tragödie in einem Akt

Musik von Richard Strauss (1864–1949)

Uraufführung: Königliches Opernhaus Dresden, 25. Januar 1909

Vollständiges Libretto von Hugo von Hofmannsthal nach seiner Tragödie (1903), die auf der Elektra (ca. 420 v. Chr.) des Sophokles basiert

Musikalische Leitung | Alexander Soddy · Inszenierung | Harry Kupfer · Bühne | Hans Schavernoch · Kostüme | Reinhard Heinrich · Choreinstudierung | Martin Schbesta

Klytämnestra | Nina Stemme · Elektra | Aušrinė Stundytė · Chrysothemis | Camilla Nylund · Aegisth | Jörg Schneider · Orest | Derek Welton · Der Pfleger des Orest | Marcus Pelz · Die Vertraute | Ana Garoticj · Die Schleppträgerin | Maria Zherebiateva · Ein junger Diener | Hiroshi Amako · Ein alter Diener | Dan Paul Dumitrescu · Die Aufseherin | Stephanie Houtzeel · Erste Magd | Monika Bohinec · Zweite Magd | Juliette Mars · Dritte Magd | Teresa Sales Rebordão · Vierte Magd | Anna Bondarenko · Fünfte Magd | Regine Hangler · Erste Dienerin | Maria Isabel Segarra · Zweite Dienerin | Seçil Ilker · Dritte Dienerin | Jozefina Monarcha · Vierte Dienerin | Dymfna Meijts · Fünfte Dienerin | Karen Schubert · Sechste Dienerin | Sabine Kogler · Orchester der Wiener Staatsoper · Chor der Wiener Staatsoper · Komparserie der Wiener Staatsoper

(For further informations) Link to the Wiener Staatsoper website: Elektra