Above all, I respected the character and life of my characters; I wanted them to express themselves outside of me, outside of themselves. I let them sing in me. It was in these terms that Claude Debussy defended Pelléas et Mélisande in the pages of Le Figaro on 16 May 1902, after the première of the lyric drama at the Opéra Comique on 30 April of the same year. Polemics of all kinds erupted from all sides and the composer, rather discreet, was invited to express his views on the composition and the choices he had made for his (only) opera. More than 70 years later, the piece is performed for the first time at the Opéra Garnier in a production staged by Jorge Lavelli with Richard Stilwell (the first Billy Budd at the Metropolitan Opera) and Federica von Stade (one of the 20th century’s greatest connoisseurs of the French mezzo repertoire) in the title roles. It took a few more years (20 to be exact) for it to return to the stage – this time at the Opéra Bastille – and here it was a resounding success: Bob Wilson’s 1997 staging, revived in 2012, has left a indelible impression, combining its stripped-down vision with a story that, both theatrically and musically, demands only the utmost delicacy.

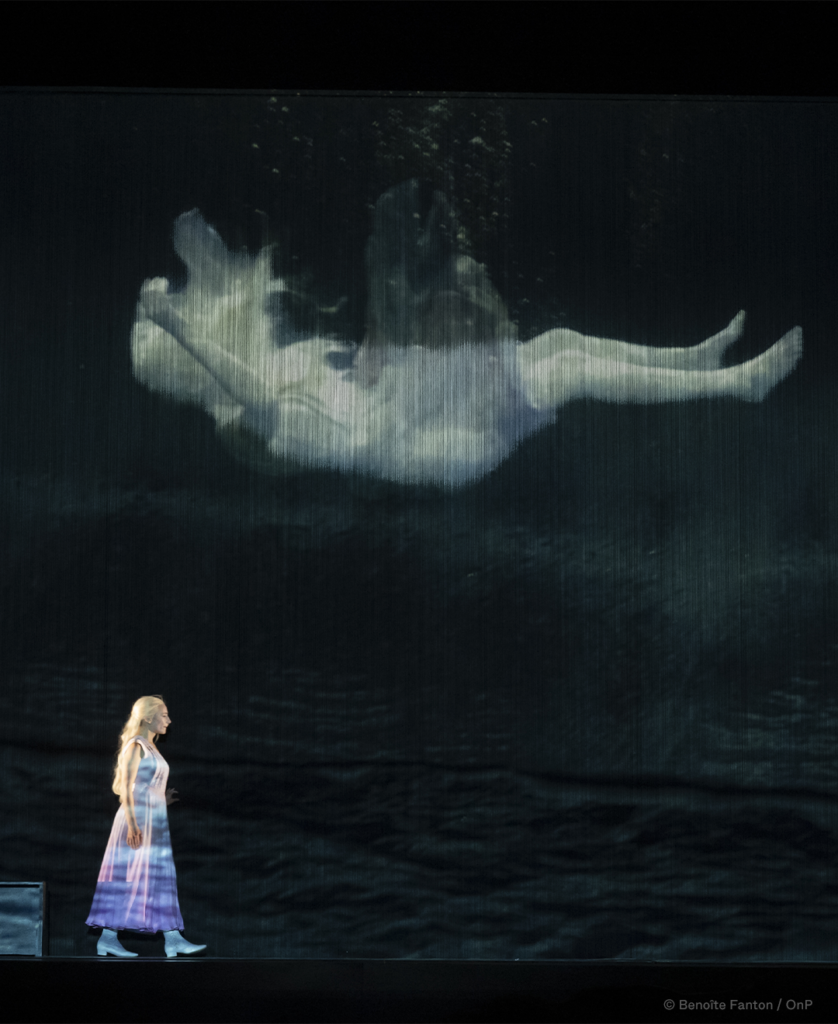

Considering the historical background to this opera, marked by its ups and downs in terms of both staging and recording, the Pelléas offered this season by the ONP, according to Wajdi Mouawad’s scenic vision and Antonello Manacorda’s musical interpretation, is a small piece of jewellery that we would like to keep for a long time. We realise, from the opening moments, that it will all be a question of symbolic evocation (any attempt at exhaustiveness in this review would be fruitless), such as that of Mélisande’s hair, through the curtain of threads juxtaposed against each other – creating a screen on which different landscapes succeed and recount what we do not see but suspect, thanks to the incantatory music emanating from the pit. This same curtain serves as a porous membrane between the action unfolding before our eyes and a world inaccessible to the audience, where what we see reverberates. Here, too, perfect synergy between stage and orchestra: with conducting that encompasses extreme modesty to the most bewitching sensuality (always a little chastity), under the almost liturgical impetus of A. Manacorda, with his deliberately restrained (but systematically expressive), creates a tableau that never holds back the light – this diaphaneity will be a constant throughout the opera – and whose juxtaposition of assemblies (within and outside the 5 acts) ensures that sensation, never denied, of continuity of discourse (strongly desired by Debussy). The score is chiselled with unrivalled finesse, perfected down to the tiniest detail (the interludes are of meticulous and unreal beauty), stretching and shrinking with the same suppleness of the threads that suggest Mélisande’s hair; a long, more or less peaceful river that flows along geometrically adjusted trajectories, according to the emotions of the characters.

The cast is of the highest calibre, and in itself an event in its own right: Huw Montague Rendall, full of poetic charm, with a remarkable articulate, combining declamation and singing with unparalleled acuity, with the right balance at every turn, credible at every moment, is, in short, the best Pelléas of recent years. In Sabine Devieilhe, he finds a Mélisande to his highest standards: at the zenith of her ample (but still ethereal) resources, with a luminous timbre and sophisticated modulations, we perceive that the psychology of the character is the fruit of a refined construction touching on both the senses and the intellect. A certainly indelible souvenir of his Mes longs cheveux descendent jusqu’au seuil de la tour. Gordon Bintner’s Golaud is coated in power, resulting in a muscular projection that is repeatedly animated by an irrepressible primitive force, capable of exterminating brutality, but we would have liked to see a more gradual (and above all more palpable) transition to the fragility demanded by the story, particularly in Act 5. And to have Jean Teitgen as Arkel (we have rarely listened to such a tender bass, without losing his authority) and Sophie Koch as Geneviève (deeply human and fraternal, characteristics enhanced by the humility that only great performers can radiate on stage) is pure delight.

One of the rare critics to come to the defence of Pelléas on the occasion of its première was Henry Bauër, who predicted in the Figaro of 5 May 1902: Today or tomorrow, Debussy’s score will become a dominant work. It’s a matter of time, not much time. […] Before many years, […] you will consecrate (with the regret of not having been among the first in the theatre) this work, so passionately artistic, so young, so pure and tender, so original in subject, inspiration and expression. More than 100 years later, we can only confirm this prediction – adding that what we are seeing at the Opéra Bastille in this moment is worthy of the best that we have seen/listened to in the last 20 years in the history of Pelléas et Mélisande in the matter of staging, casting and musical direction.

Casting: Pelléas (Huw Montague Rendall), Mélisande (Sabine Devieilhe), Golaud (Gordon Bintner), Arkel (Jean Teitgen), Geneviève (Sophie Koch), Yniold (Anne-Blanche Trillaud Ruggeri), Médecin (Amin Ahangaran). Orchestre et Choeurs de l’Opéra National de Paris.