It is perhaps the opera that moves me the most. These are the words chosen by Alain Duault at the beginning of the section dedicated to Rosenkavalier in his Dictionnaire amoureux de l’opéra. We could well have been the originators of this phrase, especially after witnessing the new production at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées.

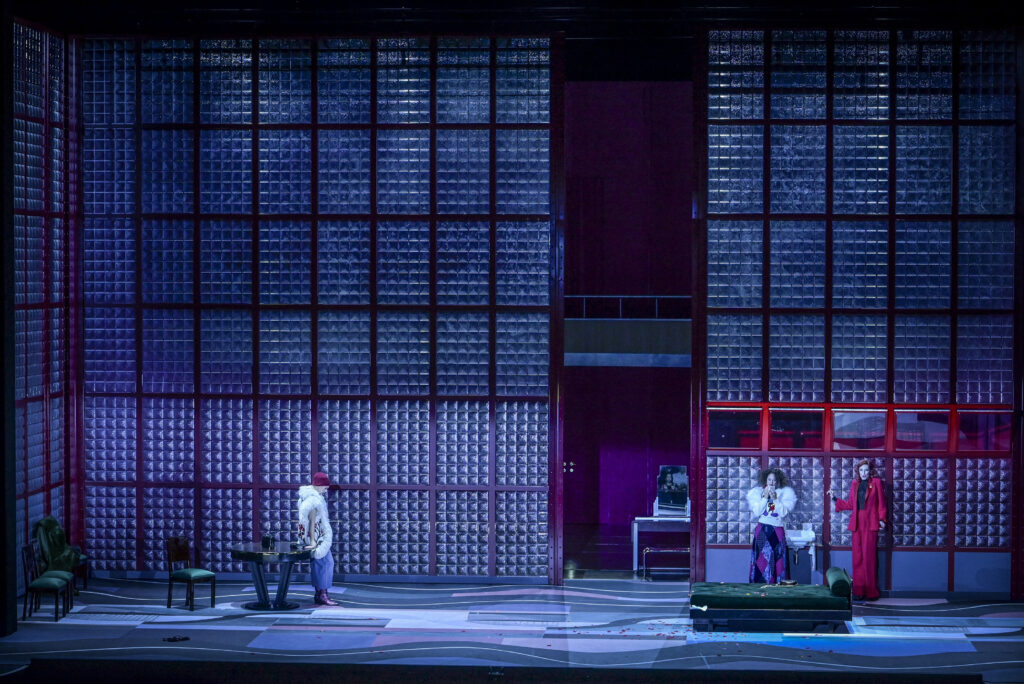

According to Krzysztof Warlikowski’s vision (executed with remarkable precision), the setting unfolds somewhere between Paris and Bavaria, in a period spanning from the 1960s to the early 2000s. The scenography (signed Małgorzata Szczęśniak) serves as a poignant reminder that the narrative to be presented is not merely the product of the librettist’s and composer’s imagination, but rather a fragment of the broader human comedy, capable of resonating with anyone’s experience. At its heart lies the waning love story between two women, separated by an age difference that, while left unquantified, is nonetheless plainly perceptible. The elder, a certain Feldmarschallin (Véronique Gens), is a celebrated star (of theatre, cinema perhaps? The distinction is incidental) whose career, though widely acknowledged, is no longer at its zenith. Her younger counterpart, Octavian (Niamh O’Sullivan), may not command the same prestige, yet navigates and flourishes within the same milieu with effortless ease.

Their relationship is no longer what it once was – the more seasoned of the two senses a growing distance creeping inexorably closer. Beyond the natural wear inherent to any romantic bond, she is acutely aware that a certain factor, one that may aggravate the situation to varying degrees, must be taken into account when assessing the reasons behind this fading intimacy. This disparity is not merely one of age, but of differing perceptions – of life, of people, … Mere sorrow over the impending dissolution of their union is not enough: the environment itself must twist the knife, relentlessly reminding her that she is no longer the woman she once was, and that the future will offer no opportunity for her to reclaim what has irrevocably passed. To heighten the poignancy of this emotional turmoil, let us add a layer of exuberance, a veneer of superficiality, and even a touch of luxuriance: a milieu where everything is one tone above excess.

These elements help to infuse the work with an air of decadence – the very essence Hofmannsthal sought to imbue by setting the opera against the backdrop of Vienna during the reign of Maria Theresa. As for the trio of the Feldmarschallin/Octavian/Sophie, the focus is less on moral decline (so vividly embodied by Baron Ochs, masterfully portrayed by the excellent Peter Rose, alongside the embodiments of tabloid sensationalism, fiercely defended by Eléonore Pancrazi and Krešimir Špicer) than on the inevitable reshuffling of fate’s deck, dictated by the often unpredictable passage of time. It is precisely in her decision to grant Octavian the freedom to embrace his independence as he sees fit that the Marschallin exacts her quiet triumph over the whims of fate. She accepts the inevitability of their parting (recognising, in the second act, that regardless of her own will, the conditions she herself has set in motion will inexorably facilitate this imminent conclusion). She even resigns herself to returning to her home and continuing her rather cheerless existence alongside her husband, yet only once she has exercised her agency in consenting to this outcome. This lends an undeniable intensity to her reappearance in the third act and imbues the final trio with profound beauty. Despite the superficial frivolity suggested by the set design, the costumes, and the exaggerated caricature embedded in the characters’ mannerisms, this production reveals a depth of meaning that meticulously honours the opera’s intent – both its overt declarations and the more elusive nuances discernible upon a careful reading of the libretto.

Any attempt at an exhaustive description of the vocal performances in this magnificent production would ultimately be futile: each singer, meticulously selected, has dedicated themselves to shaping their character with the utmost theatrical depth, seamlessly intertwining it with the vocal identity traditionally associated with these beloved roles. From Véronique Gens, one can expect an unshakable dignity, underpinned by the vocal solidity of a seasoned Mozartian, finally granting us the joy of hearing her in the finest of the Strauss repertoire. Niamh O’Sullivan embodies fervour, youth in full bloom, effortlessly navigating the entire vocal spectrum of an Octavian more mature and assured in their strengths than is customary. Regula Mühlemann proves to be the ideal interpreter of a Sophie whose evolving demeanour is accompanied by a vocal purity that remains steadfast throughout. Peter Rose, with his warm and resonant voice, effortlessly embodies Ochs, his deep familiarity with the character shining through with striking immediacy.

Jean-Sébastien Bou and Krešimir Špicer astonish with the sheer power of their voices, while Eléonore Pancrazi proves delightfully insufferable as the instigator: her effortless high notes adding to her captivating presence. Francesco Demuro (what a luxury!) embraces both the director’s and composer’s vision, delivering a tenor steeped in irony. Laurène Paternò showcases remarkable vocal agility, bringing to life a Marianne as credulous as Sophie, rooted in the purity of a love that ultimately finds its way. From the orchestra pit, the balance within and between the ethereal passages and the surges of impetuosity dictated by the score does not always align with expectations. Yet, on the whole, Henrik Nánási successfully harnesses the many strengths of the Orchestre National de France, elevating the most poignant moments of the libretto to sublime effect.

Is this an overly extravagant perspective or one that verges on undue audacity? We don’t think so. Is the approach provocative? For some, undoubtedly. Does it deviate from the essence of the work? By no means. This perspective lacks neither legitimacy nor intelligence, nor humour, which is, in itself, an undeniable testament to intellect. All these reasons ensure that this production commands our attention, not only today but in the future. Proposals of this kind are more than necessary to remind us that opera is, and will remain, an art form that will never cease to astonish, and to move us.

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

DER ROSENKAVALIER

Comedy for Music in three Acts by Hugo von Hofmannsthal

Music by Richard Strauss (op. 59)

Henrik Nánási | direction · Krzysztof Warlikowski | staging · Małgorzata Szczęśniak | scenography and costumes · Claude Bardouil | choreography · Felice Ross | lights · Kamil Polak | video

Cast: Véronique Gens | Feldmarschallin Fürstin Werdenberg · Niamh O’Sullivan | Octavian · Regula Mühlemann | Sophie · Peter Rose | Baron Ochs auf Lerchenau · Jean-Sébastien Bou Herr von Faninal · Eléonore Pancrazi | Annina · Krešimir Špicer | Valzacchi · Francesco Demuro | An Italian singer · Laurène Paternò | Marianne Leitmetzerin · Florent Karrer | A police inspector/A notary · François Piolino | The Marschallin’s Major-Domo/Faninal’s Major-Domo · Yoann Le Lan | An innkeeper · Orchestre National de France · Chœur Unikanti, Maîtrise des Hauts-de-Seine.

(For further informations) Link to the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées website: Der Rosenkavalier (2025 production)

One thought on “DER ROSENKAVALIER | Théâtre des Champs Elysées”