This work is known for being the opera of a thousand revisions. Wagner was never satisfied with the outcome of the various versions he worked on over more than 20 years, considering that he had not given the world the Tannhäuser it deserved (or that he himself hoped to deliver). This did not prevent the opera from becoming one of the most frequently performed in Bayreuth and from having one of Wagner’s most frequently performed concert overtures. Some artists have been fortunate enough to experience phenomenal career boosts (think of Grace Bumbry’s 27 curtain calls at Bayreuth in 1960 in Wieland Wagner’s production) thanks to the characters in this mosaic of inspirations (from the adventures of troubadours who lived in the Middle Ages to the life of a saint from Eastern Europe).

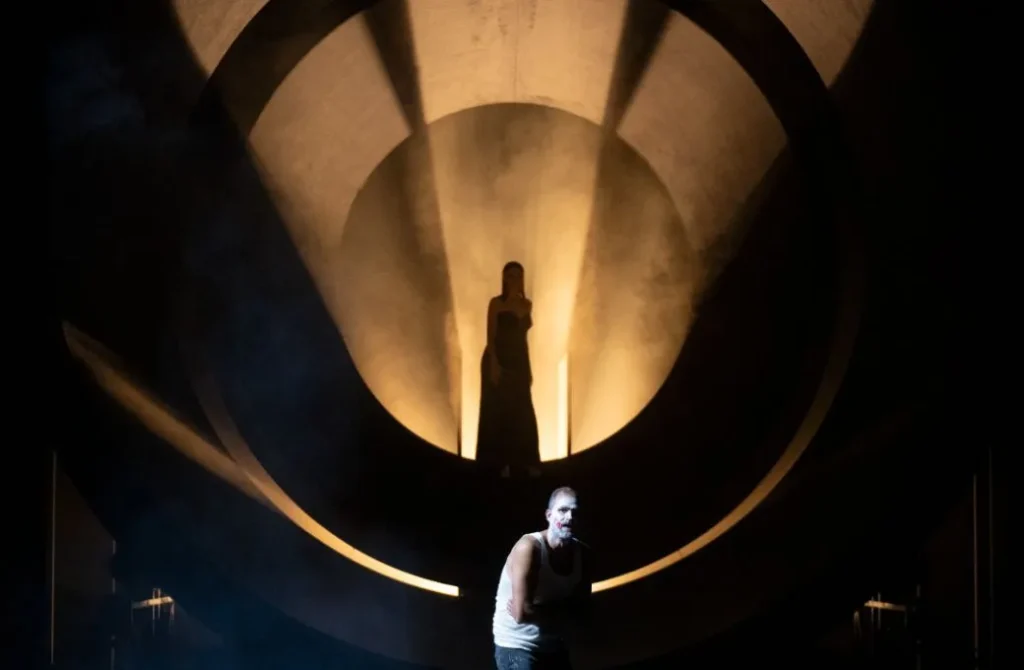

When the curtains open, Daniel Johansson is standing facing the audience. We can see in his expression the distress that will remain with him until the very end of the show: he stares at us for a long time, making us understand that his unhappiness can only be remedied by a long pilgrimage that is about to begin. The staging, by Michael Thalheimer, tells us in a very relevant way the story of this character, who resembles more a wandering Jew than a convert in search of salvation. As proof, there are two concentric scrolls, placed at the centre of the stage: the first representing the paths of the Venusberg; the second turning slowly, an inexorable march or death in which he finds himself engulfed, with its chiaroscuro accurately illustrating the moments of exaltation and downfall that the character will experience. It is a clever staging technique to tell us the whole of Tannhäuser’s initiatory journey from the outset: all his moods, the full weight of his destiny are illustrated. However, the character is not destroyed by this heaviness, and some would say that this is his ultimate condemnation. Starting with the countless unfinished efforts that Tannhäuser makes to escape from the Venusberg.

The chorus of sirens we hear at the beginning of the first act, sung by the choeur du Grand Théâtre de Genève – whose talent we cannot praise enough on this evening – with their finesse and delicacy, represent not fairy creatures, but angels with heavenly voices.

At the beginning of the second scene of the first act, we catch a glimpse of the Venusberg through the crack, which Tannhäuser struggles to keep open so that it does not close permanently. Enter Victoria Karkacheva’s voluptuous Venus. Not a hint of vulgarity: magnificent, imposing singing, reinforced by a genuine stage presence, insidious, with a dark and fierce bass when necessary. An imperious goddess who, through her enchantment, creates an aura around her beloved that reinforces the yoke under which Tannhäuser finds himself prostrate.

Daniel Johansson’s Tannhäuser has a clear, radiant voice and careful diction, colouring the words with all the intensity of his character’s intentions. He is totally committed to the theatrical embodiment of this supplicated character. His appearance and all the suffering he endures give his Tannhäuser something of a fallen Messiah, seeking repentance that continually borders on eternal damnation. The different parts of his Dir töne Lob are delivered with the same élan and vigour of the courteous singer that he is.

As Venus tries to convince Tannhäuser to stay at Venusberg, she herself becomes caught up in the character’s abyss, in his anxieties and dramas: as proof, here she is walking in an endless circle, with modulations that are sometimes energetic, sometimes sweet, even caressing, until Tannhäuser’s Mein Heil liegt in Maria! uttered by Tannhäuser makes this paradise of debauchery disappear, and with it, his Göttin der Wonn’ und Lust.

As darkness descends on the stage, a glimmer of hope resounds in the luminous song of the shepherd, played by Charlotte Buzzi. Gradually, Franz-Josef Selig’s Landgraf von Thüringen and the troubadours accompanying him appear: Wolfram von Eschenbach (Stéphane Degout), Walther von der Vogelweide (Julien Henric), Biterolf (Mark Kurmanbayev), Heinrich der Schreiber (Jason Bridges) and Reinmar von Zweter (Raphaël Hardmeyer), a perfect trope of synergy and complicity. In the background, the poignant singing of the pilgrims, who gradually approach the stage, resounds with increasing intensity in their magnificent Zu dir wall’ ich, mein Jesus Christ.

In the second act, the great troubadour hall in Wartburg Castle is revealed to be a deconstructed Venusberg, with the wheels that formed the mountain near Eisenach moved into place. We are introduced to those who will attend the singing competition through truly magical theatre, as members of a choir of great power and sublime beauty arrive from all sides. Now it is time for Jennifer Davis’ dazzling Elisabeth, with a resplendent Dich, teure Halle. Throughout her performances, fervour and docility are balanced with a sensitivity characteristic of the most sensitive and experienced sopranos. Her perfectly harmonised duet with Tannhäuser exudes both the melancholy and enthusiasm that separation and reunion inspire in her character.

Franz-Josef Selig, a German bass who comes straight from this tradition of wordsmiths who seek out words at their roots and ennoble them, intones his Gar viel und schön ward hier in dieses Halle von euch. We can only echo the knights’ words at the end of this monologue: Thüringens Fürsten Heil!

Stéphane Degout’s sublime Blick ich umher in diesem edlen Kreise (as well as his Wie Todesahnung Dämmrung decke die Lande in the third act) shows how the voice and relationship to the text of singers with the most refined artistry can transcend this wonderful passage. A moment of deep emotion, worthy of the warmest applause.

As the act progresses, Tannhäuser’s duality becomes more evident and violent. More than ever, Daniel Johansson’s vocal prowess is put to the test (as well as in the third act, during his heart rending Du, Wolfram, du sollst es erfahren), and he rises to the challenge with aplomb.

In addition to these more than impressive performances, there are those of Julien Henric, a tenor with a clear, shining voice, Mark Kurmanbayev, a deep bass with beautiful singing technique, perfectly contemptuous in the role of Biterolf, whom we eagerly await in other Wagnerian roles, and Raphaël Hardmeyer, a bass with a richly coloured timbre and inflections that blossom in the role of Reinmar von Zweter.

In the 3rd act, we discover an Elisabeth who has accepted to defile herself for redemption and out of love for Tannhäuser. Her Allmächt’ge Jungfrau, a prayer of incomparable sweetness, concludes the outstanding performance of this lyric soprano, whom we had the pleasure of seeing in the role of Arabella in Berlin a few months ago. The long duet between Daniel Johansson and Stéphane Degout reflects the dramatic tension already palpable in the libretto and offers us a moment of great beauty.

On the pit side, conductor Mark Elder has adopted a deliberately slower, more moderate tempo than what we heard on the recording. This choice greatly contributes to creating an atmosphere that is both more introspective and more poetic: whether we are at Venusberg or Wartburg, we are on sacred ground, whose sanctity is felt above all through this music, delicate as a silk cloth.

If Wagner himself had had the opportunity to see this production and hear these performances, perhaps he would have concluded that Tannhäuser was, in fact, one of the most moving works ever written.

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

TANNHÄUSER UND DER SÄNGERKRIEG AUF WARTBURG

Romantic opera in three acts

Music and libretto by Richard Wagner

Original version premiered in Dresden on 19 October 1845

“Paris” version premiered in Paris on 13 March 1861

Mark Elder | Musical director · Mark Biggins | Chorus director · Michael Thalheimer | Director · Henrik Ahr | Set Design · Barbara Drosihn | Costumes · Stefan Bolliger | Lights

Cast: Daniel Johansson | Tannhäuser · Jennifer Davis | Elisabeth · Victoria Karkacheva | Venus · Franz-Josef Selig | Herrmann, Landgraf von Thüringen · Stéphane Degoutieren | Wolfram von Eschenbach · Julien Henric | Walther von der Vogelweide · Mark Kurmanbayev | Biterolf · Jason Bridges | Heinrich der Schreiber · Raphaël Hardmeyer | Reinmar von Zweter · Charlotte Bozzi | Ein junger Hirt · Choeur du Grand Théâtre de Genève · Orchestre de la Suisse Romande

(For further informations) Link to the Grand Théâtre de Genève website : Tannhaüser

J’avais peur que ca soit une traviata bis et au final c’était plutot cool!